The last trip of the Gallego brothers

THE LAST TRIP OF THE GALLEGO BROTHERS

Jose Mena Alvarez

On January 15, 1838 at seven in the morning, what is considered the first accident of a Spanish train took place, a convoy paradoxically dragged by the Villanueva locomotive, which derailed after colliding with a bull. It happened in Cuba, at that time a province of Spain and which covered the 28 km that separate Havana from Bejucal. There were no fatalities. To find the first serious accident with deaths, we must go back to November 28, 1852, where the derailment of a convoy that fell down an embankment in the vicinity of kilometer 4 of the Madrid-Aranjuez railway, caused the death of the stoker and the inspector, as The chronicles of the time tell:

“…some travelers eagerly came to remove their companions in misfortune from that hell into which they had fallen; because that was what the ravine looked like with the smoke and the smell of coal… among those unfortunates who came out black, bloodied and fainted… the doctor who arrived at the scene of the catastrophe, Mr. Benavides, who was on duty at the hospital, and who With a confused but exaggerated news of the catastrophe, he was not afraid to get on a locomotive and fly to the aid of the unfortunates, accompanied by an assistant, a priest and several employees of the company… However, the serious state in which we find to the unhappy stoker Mr. Manuel Ortega, who survived barely three quarters of an hour… lamenting also the death of the factor Mr. Cosme Belio who has succumbed to the inflammation of the burns that the steam that escaped from the machine caused him1…”

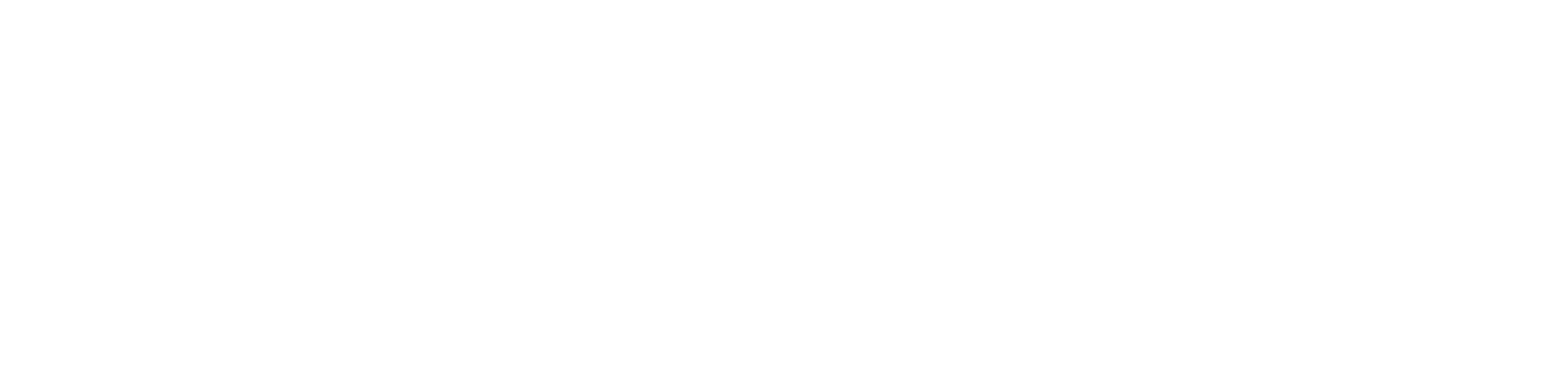

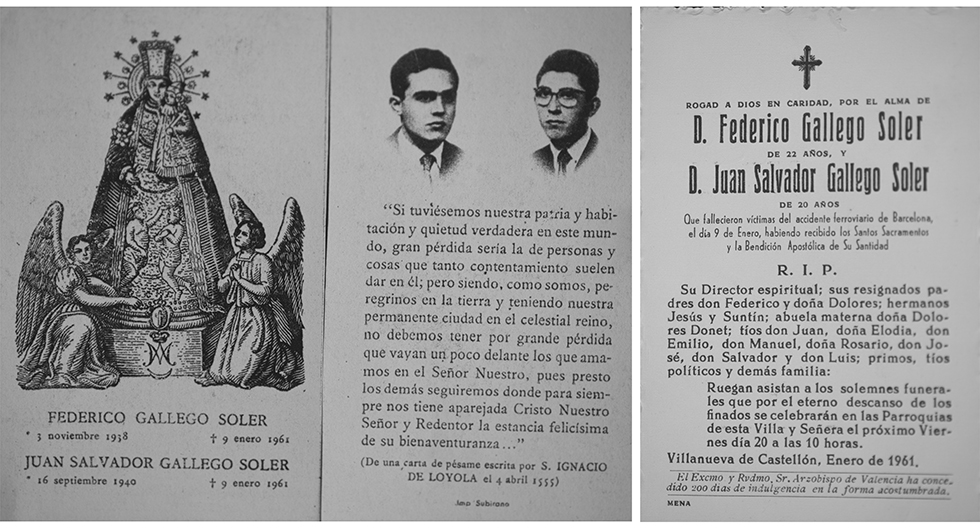

Since that last accident, 170 years ago until today, there have been some 250 accidents with nearly 3,200 fatalities. And 109 years later, specifically on January 9, 1961, the collision of the Valencia express with a freight train very close to Barcelona, left twenty-five dead. Among the travelers were four students from our town, the brothers Federico and Juan Salvador Gallego Soler, Vicente Jesus Serradell García and Justo Poveda Estrada. Last January was the sixty-first anniversary of a tragic event that shocked the whole of Spain and especially the people of Castellón. In this article we will try to remember the circumstances of that accident and to make known all the details.

.

Castellonenses who studied

At the beginning of the sixties, the fields and orchards of Castelló looked green in spring due to the rice plantations that, together with an entire old irrigation system, such as the ditches, the motors with their old chimneys and the country houses, they formed an exclusively agricultural landscape at a time when the Ribera, with the exception of some emerging company of the time, depended almost solely on what the land gave. In this rural setting, the children of the vast majority of families in the town were forced to follow their parents’ trade. However, there were some who could give studies to their descendants. This was the case of the brothers Federico and Juan Salvador Gallego, of Vicente Jesus Serradell – all three had studied at the prestigious Jesuit school in Valencia – and of Justo Poveda.

After finishing secondary education, Federico and Vicente Jesús moved to the Chemical Institute of Sarrià, Barcelona to study Technical Engineering, while Justo Poveda, with fewer financial resources and living in a boarding house -also in Barcelona- had begun his medical studies. About Federico, the older of the two brothers, his niece María Jesús tells us that he was a very constant young man, as well as simple. At all times he advised his brother Juan Salvador, who was more prone to more unrealistic dreams, and for this reason he decided to take him to Barcelona and have him study there for the Quantity Surveyor, since the last course had not been focused at all: he used to go with friends and he did not study, as was his duty.

However, the same fate awaited both of them that no one could have imagined and with which the human being does not usually take into account. One day, like any other, death and the end of so many projects awaited them on the tracks. At the time of the accident, Federico was 22 years old; he was in everyone’s eyes an enviable young man. At that time he was about to finish his degree in Chemical Engineering, he hoped to join the university militias and had already signed a contract with Nogueroles (Germany) to work as soon as possible. His brother Juan Salvador, 20, was preparing to enter the Superior School of Quantity Surveyors, following the path marked out by his brother.

At the end of 1960, the Gallego brothers returned to the town to spend, without knowing it, the last Christmas with their family. Nobody could think that they would take the last goodbye. They did it by plane, and it was not exactly a very pleasant experience. Arriving at the Manises airport, due to the strong wind, the aircraft had to circle the runway several times before landing. Federico was very scared and so he transmitted it to his father and, although they had bought the return tickets, they decided that they would return to Barcelona by train.

The accident

On the night of January 8, 1961, the four students from Castelló left together on the town’s trenet, where Juan Salvador, who had taken a little too long to say goodbye to his girlfriend, arrived practically with the train running and almost lost it. , Justo lamented when I interviewed him. They arrived at the Nord de València station, where they were scheduled to leave at 11 p.m. with the express destination Barcelona. Federico, a few moments before, in a premonitory way, bought a book entitled My last trip, where you could read: “Don’t feel sad for me, I’m sure that wherever I go there is no suffering. Open a bottle of your favorite drink, and remind me when I was good, when I laughed with you. Make a toast with me, because wherever I am I will raise a glass, for all of you who crossed my path”.

He was just traveling in third class, but he went to the second class car where Federico, Juan Salvador and Vicente Jesús were to chat with them. And right at the entrance to Tarragona she fell asleep and went to rest in his car.

Monday, January 9, 1961, was a gray and cold day. At some station you could hear Johnny Tillotson’s Poetry in motion, a song of the moment throughout Europe. Around twenty-five minutes past seven in the morning, at the Casa Antúnez fork in Hospitalet de Llobregat, the tragedy occurred. A CB-1 freight train made up of empty flatcars coming from Sants station collided head-on, with terrible violence, against the express train coming from Valencia. The brutal impact caused the freight train’s electric locomotive to overturn onto the right bank a considerable distance from the crash site, while the express locomotive remained upright resting on its rear. Part of the rest of the passenger convoy was turned into a jumble of iron and wood, with a total balance of twenty-five dead and fifty wounded.

On the freight train, which was traveling at about 30 km/h, were the driver Fernando Benavente Molero, and the assistant driver Antonio Ávila Lloret, 58 years old. Three hundred and sixty people were traveling on Express 704 in Valencia, divided between locomotive 7652 with simple electric traction, a baggage van, the boiler car and six passenger cars distributed as follows: first class metal car (number 6138) 2nd class metal mixed seating car (No. 1030), second class wooden passenger car (No. 2366), two third class metal cars and one metal sleeping car. The accident took place at kilometer 672,900 of the railway line, near the Castelldefels motorway and near the Bellvitge hermitage, in the municipality of Hospitalet de Llobregat.

It seems that the event was due to a human error caused by the driver of the Valencia express, Fernando Ruíz Noriega, who did not notice the two yellow light signals warning of the needle crossing of the level crossing at the exit of the L’Hospitalet station that, in a staggered way, forced to slow down. The train continued to circulate at route speed, about 80 km/h, until it noticed the red danger signal that forced it to come to a complete stop. When the brakes were finally activated, there was no longer enough time to avoid colliding with the cargo. As a result of the brutal impact, Fernando Benavente Molero, Jose María Palleja Sangenís and 32-year-old Jose Luis Maroto Echevarría -machinist, train chief and goods railway manager respectively- were killed and were imprisoned among the locomotive’s scrap metal, while Antonio Ávila Lloret was seriously injured. Nicolás Fernández Fernández, assistant to the express, a native of Arbucinos (Zamora), was crushed inside the cabin and was not released by firefighters until seven hours later with the help of cables dragged by a crane car that separated the plates that had destroyed it. and Jose Gutiérrez Jiménez, 30 years old, in charge of the boiler of the express, the discovery of his dead body was possible by putting out the fire that had occurred inside the wagon, while the driver Fernando Ruiz Noriega was seriously injured when he was fired .

The fact that metallic units were alternated with wooden ones among the passenger carriages apparently contributed to increasing the number of victims. The mixed car, with a metallic structure, entered the wooden one that followed it and reached the height of the ninth window. The car was left undone and full of corpses. Also among the passengers of the metal unit, several people were injured as a result of the deformation suffered by the car and the numerous sparks that entered. As for the rest of the wagons, the first unit also appeared several affected, while in the rest, it seems, there were only minor bruises and contusions. One of the convoys partially demolished the level crossing signal booth and seriously injured the switchman.

Among the victims of the express passengers, all located in the wooden car, were nine students and a teacher who were traveling to Barcelona after the Christmas vacation period. Father Ferrer Pi, director of the Chemical Institute of Sarriá, accompanied by the deputy director, Father Sanz Burata and the priest Luís Corví, identified Fernando Rubio Verniers, from Valencia, 24, a graduate in Physics, who was preparing his doctoral thesis . Likewise, they identified the bodies of the brothers Federico and Juan Salvador Gallego Soler from Castellón, the student Rafael Ruiz Beltran, 22, a native of Alzira; Jose María Martinez Soler, 20 years old, future quantity surveyor, from Benimamet; Rafael Ortega Giner, 21, a native of Castellar (Valencia), also a surveyor project; Jose del Hoyo Arcajarán, 61, from Valencia, national teacher and resident of Vic; Amparo Barado Sánchez, 22 years old, pharmacy student and native of La Unión (Cartagena); Rogelio Pagés Giménez, 19 years old, a native of Escuyas (Almería), son of the RENFE factor, stationed in Sitges; Jaime Cañellas Fornés from Palma de Mallorca; the brothers Gonzalo Villalba Aguilar and Miguel Villalba Aguilar, aged 7 and 5 respectively, and their parents, Miguel Villalba Palomar and Amparo Aguilar, from Segorbe, who died in the ambulance during the transfer to the hospital; Emilio Sapiña Zapates of Barcelona; Eleodel Gutierrez Martín, train driver for RENFE, Tarragona; Ana Garcia, 31 years old. There were also two young and outstanding students from the Higher Technical School of Industrial Engineers (Textile Section) of Tarrasa: Mr. Luis Juan Gisbert Vicens, 19 years old, a native of Alcoy, nephew of the Civil Governor of Madrid, and Mr. Juan José Rodoreda Artasánchez, from 18 years old, born in Puebla (Mexico), second-year students, dear friends as well as exemplary students -Rodoreda was number 1 in his promotion and Gisbert one of the best in the course- and they had moved to Valencia to spend the Christmas vacations at Gisbert’s house, and when the catastrophe occurred they returned to Tarrasa to join their studies.

But the accident could have been greater, since the incident caused the fall of the electrical cables of the railway traffic control tower, which, luckily, did not cause any damage to the surviving passengers. The emergency services immediately went to the scene of the accident: firefighters from Barcelona, the Red Cross, Armed Police, Civil Guard, as well as different authorities from Hospitalet and Barcelona. The rescue work lasted well into the night, although the first aid and aid to the injured came from the hands of the train passengers themselves, from numerous residents of L’Hospitalet who approached the scene of the accident and even from several workers from the La Seda factory in Barcelona, in El Prat de Llobregat, who moved to the site with electric torches to help the firefighters in the rescue actions. Around 1:00 p.m., the team made up of Dr. Masoliver and four other doctors injected blood serum into two young women trapped inside a wagon, and finally, after great efforts -by the firefighters- they were released with serious injuries along with to another man. After four in the afternoon, about ten hours after the catastrophe occurred, the firefighters broke the iron of the metal car with an electric torch, and extracted the bodies of seven other people.

The R.C.D Español expedition was traveling in the express on the sleeper car, returning from playing a match in Mestalla for the National League Championship, which they lost 3-0. The masseur, Mr. Fernández, who accompanied the expedition, improvised an emergency kit to help, together with the player Torres, numerous wounded. Regarding the blue and white expedition, coach Ernesto Pons declared:

“Suddenly we have noticed a very strong shake, followed by braking, which has been repeated two or three times, until the convoy has stopped in about six meters. As a consequence of such a stoppage, we have all fallen to the ground, one on top of the other, but we have got up immediately, without giving it importance, having the impression that someone had pressed the alarm bell and the train had stopped, in a even exaggerated. We have opened a window and we have not seen absolutely anything abnormal or extraordinary, but it has occurred to me to go down and I have been impressed to see the collision with a goods and the tremendous damage. Our first three cars and the engine were materially embedded in those of the opposing train… Some cars were on top of others in splinters and that was a heap of twisted iron, wood, blood and high-pitched wails… For our part, everything has been reduced to small blows and the consequent scare when getting off the train and realizing the dramatic magnitude that such a phenomenal crash had. All of us, together with the masseur Jaime Fernández, have collaborated in the rescue of the victims and to treat or provide first aid to the injured”.

Justo and Vicente Jesús

Among the multiple stories of the survivors of this accident, we find those of the husband and wife from Alicante -made up of Carlos Torra and his wife-, who canceled the trip and sold the tickets shortly before the train left; or that of Vicente Ballestero, 28, who was traveling in the wooden module, on his way to England, where he hoped to marry his girlfriend, Amparo Hernández. Hearing the noise, Vicente and Jose Montero who accompanied him quickly threw themselves to the ground, where they were imprisoned by an iron bar. After being rescued, with minor injuries, the students, all of them Valencians, Juan Palomares, Salvador Vendrell, Vicente Meseguer, Manuel Cortés, Salvador Verdaguer, Vicente Domínguez and Justo Poveda also intervened in the rescue and aid work for the injured. , that they made the trip to the 3rd class carriage because there were no second class tickets left, and that when the collision occurred they slept in their compartment and were aware of the crash so that the suitcases fell on them, as soon as they could they left the carriage to help, especially to the passengers of the second-class car where most of the victims were registered. Justo Poveda, who got off the train right away, told me with a lump in his throat:

“When I went down I found a dantesque scene, everywhere there were remains of the convoy, luggage, torn clothes, shoes and other personal belongings of the injured travelers, surrounded by smoke and the cries of the injured people: a real chaos. I went running to look for my companions, and when I got there, -here, while he tells me, a lump forms in his throat and he stares blankly for a few seconds-, that wooden wagon, in which some Minutes before I had been chatting with them, an accordion was made. The metal wagon that was following him had embedded itself in it and had killed everyone with the exception of Vicente Jesús Serradell, since he stayed at an angle, when the wooden wagon moved at the last moment, making a wedge, a kind of hole. He was very lucky and I was very happy to see him. Trapped as he was by his legs, he repeated to me: << They’re all dead, they’re all dead! >>, I turned my head and indeed I didn’t see or hear anything, just a pile of twisted iron and wood splinters. Vicente Jesús told me that seconds after the impact he could still hear Juan Salvador’s plea for help and calling his brother Federico. As soon as I could -he continues- I took him out the window and carrying him on my back I took him to the road”.

Despite the high number of victims and injuries, the magnitude of the collision could have been of greater importance, given that the number of passengers traveling on the Valencia expressway amounted to some 360 people.

Balbina Vert, a resident of Castelló who lived in Barcelona, was the woman who washed the brothers’ faces when their bodies arrived in Barcelona to perform autopsies

The burial of the Gallego brothers

On Tuesday, January 10, 1961, at five in the afternoon, solemn funeral services were held for the victims in the L’Hospitalet de Llobregat cemetery. The ceremony coincided with the completion of the autopsies carried out on the corpses, which were deposited in coffins in a line on the esplanade of the cemetery, where family and friends went. Minister Mr. Pedro Gual Villalbí presided over the act accompanied by numerous ecclesiastical, university and political authorities. Later, the deceased were transferred to their places of origin to receive a Christian burial. That same day classes were suspended in the different university faculties as a sign of mourning for the nine deceased students. The transfer of the corpses of the Valencians was moving. The ardent chapel was initially installed at the Nord station. There were funerals in Valencia, Alzira and Castellón. The burial in our town was presided over by the civil government and a good representation of the Jesuits of Valencia:

“Solemn funerals have been held in our parish temple in memory of the brothers Federico and Juan Salvador Gallego Soler, victims of the railway accident that occurred in the Antúnez house. The church was completely occupied by the faithful. The parents of the victims, brothers, uncles, authorities and other relatives presided. Our reverend parish priest Dr. Gallart y Miquel officiated, assisted by Don Vicente Cifre and Juan Lluch, both seminarians who were sons of this town. The parish choir performed under the direction of maestro Don Eduardo Cifre Gallego, who masterfully interpreted the Misa of Obitus, for two voices, by Valdés. In the response, Perosi’s “Libérame Dómines” was sung, with three great voices. At the end of the mass, the parents and closest relatives received the condolences of all the attendees, who once again testified to the great pain felt by the people of Villanueva de Castellón for the irreparable loss of these two brothers who died in such a tragic event. ”.

Memory and hope

At no time is death a companion desired by anyone, least of all in the period of youth full of dreams. It is expected and understood if it occurs after a long life, but it is unwelcome if it is sudden and life is about to begin. The life of our people was dyed in mourning in those days and the memory still lingers. At least his family and those who were friends and acquaintances have not been able to forget that fact. As the French writer Alphonse de Lamartin (1790-1869) used to say, death always has two faces, that of the one who leaves and that of those who feel the pain of goodbye: “Often the tomb closes, without knowing it, two hearts in the same coffin. In any case, surely those who are leaving would give us a message of hope if they could, as the North American Mary Elizabeth Frye (1905-2004) well insinuates:

No te detengas en mi tumba a llorar.

No estoy ahí, no estoy dormida.

Soy un millar de vientos que soplan,

soy la suave nieve que cae,

soy las gentiles gotas de lluvia,

soy los campos de granos maduros,

estoy en el silencio de la mañana,

en la prisa agraciada

de hermosas aves que vuelan en círculo.

Soy la estrella de la noche,

estoy en los pétalos que florecen,

en un cuarto silencioso,

en los pájaros que cantan,

en cada pequeña cosa.

No te detengas en mi tumba a llorar.

No estoy ahí, no estoy muerta.

1 https://prensahistorica.mcu.es/es/catalogo_imagenes/grupo.do?path=1001533745